Groves’ ORIGIN Congealed Oil Varnish (65 mil. glass jar)-- Now available in linseed oil or walnut oil-based versions

For oil painting in a tempera-like manner.

For my enlightening research into the exact nature of Rubens' turpentine solvent, go

here.

]

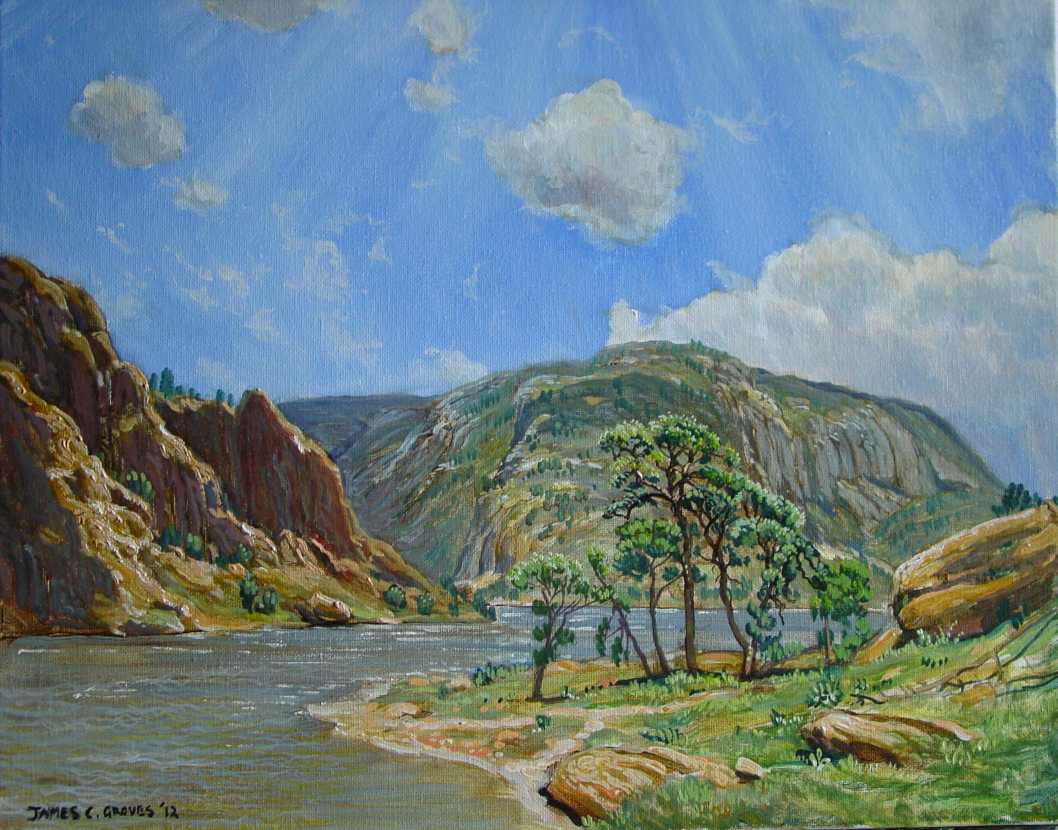

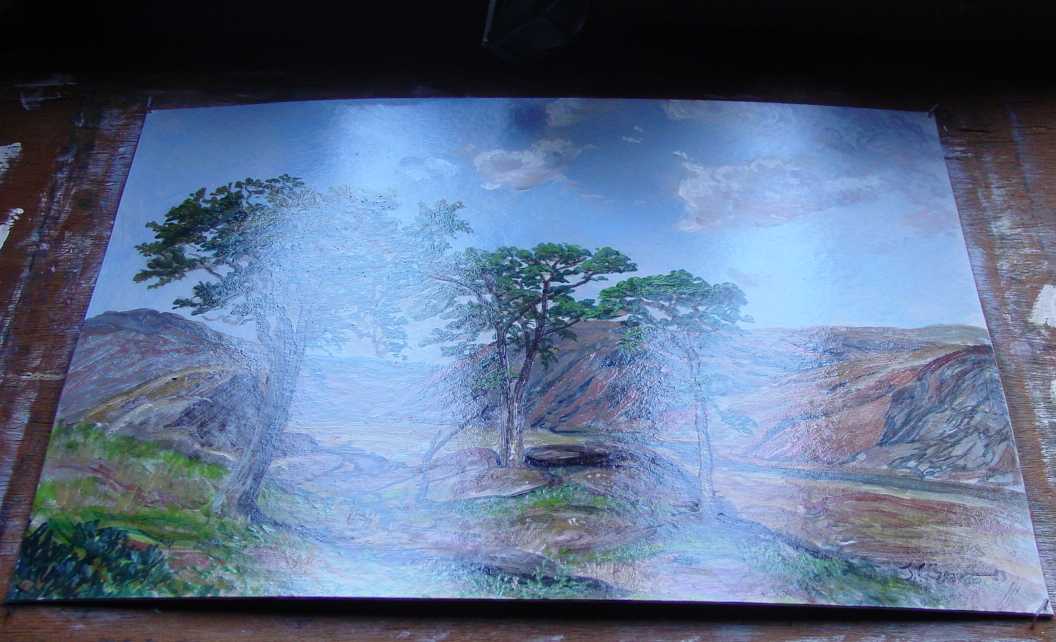

"Abandoned Surface Mine; December Morning in the Lower Georges Creek Valley, Western Maryland"

Oil painting by James C. Groves, February, 2013.

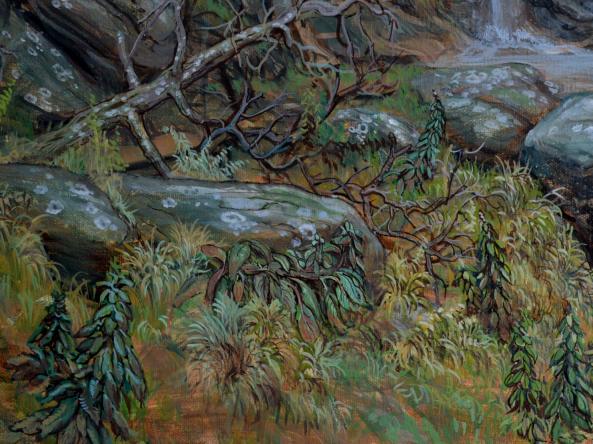

The above highly-detailed painting was created using a tempera-like solvent-technique coupled with ORIGIN Congealed Varnish. The painting measures 24 x 30-inches and was completed over a period of two weeks. The tightly-rendered paint dried with a gloss and did not require a final varnish. The amount of ORIGIN Congealed Varnish needed to create the entire painting amounted to about 1/4 inch of the jar.

Above: A closer view of the 24x30-inch painting; right foreground.

Above: Another detail; left foreground.

As these details show, the surface of the painting is perfectly receptive to in-painting using a tempera-like manner. This means the tinyest ink-like lines can be inserted at any time with ease and fluidity ... and with no 'skip'. Additionally, the act of blending using the solvent is ideally suited to the faintest gradations in coloring and modeling. This simple action is a valuable asset for the traditional painter. This ability to physically "meld" set-up paint-layers together is not available to regular oil-bound painting or egg tmpera painting; nor is this action available to the painter using combined egg-with-oil emulsion paint and technique (AKA "tempera grassa").

Above image: ORIGIN Congealed Varnish (or "ORIGIN") is a firmly-congealed coniferous resin-and-oil varnish of amazing clarity and binding power. ORIGIN is intended to be utilized in conjunction with dry pigments to create a unique varnish-bound paint. When paint is created using ORIGIN varnish, pigment, and a preferred solvent, a tempera-like manner becomes available to the oil painter. Paintings made using ORIGIN exhibit a brighter coloration which does not yellow, even when stored in darkness. Paintings dry with a gloss and do not require varnishing for a very long time. Kept at room temperature, ORIGIN will remain in its firmly-congealed state for approximately two-to-three-months; however, storing ORIGIN in a cold refrigerator between use allows it to remain perfectly congealed and viable for a year and more. ORIGIN also contains an essential oil (gum-spirits of turpentine) and requires the use of a solvent such as paint thinner, naptha, turps, spike, Rosemary, limonene or other diluent, during the painting process. Individuals who have experienced negative reactions to turpentine and other solvents/spirits should avoid this product (as well as Fir Wax).

Heat-Bodied Oil VS Bodied Oil ... and Pine Resin

Modern-day analysis of certain old master paint-chips shows frequent use of something called "heat-bodied oil". This finding or clue indicates an oil that has been thickened in consistence through the action of a high-temperature 'cooking', such as the actual physical boiling of the oil -- which begins to occur around 570 degrees F. Besides this high-temperature boiling, there are other methods of thickening painting oils; however, oils thickened (bodied) by oxidative exposure, such as to air and sunlight, or to low heats for extended times, will not produce a signature of heat-bodying. Instead, such oxidatively-produced thickened oils will likely show only their oil-type, such as linseed or walnut. There really is no way to betray how such oils became thickened, or if in fact such oils truly were thickened, at all.

It is important to understand something else: A signature of heat-bodied oil will also show itself when a high-temperature-produced oil-and-resin "varnish" is (or was) added to the oil paint. Be it known, some oil-resin varnishes require to be 'cooked' to a very high temperature in order to combine the resin ingredient with the "varnish-oil" (which was usually a thickened oil). Such hi-temp varnishes would be amber varnish, copal varnish, or sandarac varnish. Heating the resins to such high temperatures simply destroys their original 'finger-prints', or what is more commonly termed "markers". Most every other resin besides amber, copal, and sandarac, can be joined with a varnish-oil via the use of lower heats, and some of these heats may not totally destroy the resin's inherent "markers". Anyway ... it should be understood that a test-finding of "heat-bodied oil" in an olden paint-chip does not necessarily preclude the addition of amber or copal or sandarac, or other resin/s within the whole. In other words, what appears to be "heat-bodied oil" may, in fact, be an oil-and-resin varnish, instead.

Now here is something I find quite interesting: Current anaylsis of Jan van Eyck's oil paint gives-off findings of heat-bodied oil which often includes a slight addition of pine resin*. Aside from the pine resin and H-B oil, there appears to be absolutely no other oil-ingredient within the mix -- no "raw" linseed, no walnut oil, no-nothing. I repeat: The only sort of oil is heat-bodied ...with some traces of pine resin. This bodied-oil-and-pine resin-mix shows within some paints, in particular glazes, where this binder would be used in relative abundance (compared to leaner pigment-heavy paint); and also within the clear (un-pigmented) coatings --which coatings are found between some layers of paint and as a final-covering atop the paint, itself. [* For example, see here: ]

Yes, that is a very interesting finding to my mind ....because this finding could very likely mean Jan van Eyck's paint-binder was an oil and resin combination, otherwise known as a "varnish"; and more specfiically as an oil-resin varnish.

Traditional oil and resin varnishes, such as were commonly used by artists/craftsman, were made using a resin and cooking that resin into a bodied or thickened oil (either aged, or sunned, or literally boiled to its thickened state). Why a bodied oil? Well, such 'heavy' oils are tougher than simple raw un-bodied oil, for as such oils thicken and become concentrated in make-up, they also become very water-repellent. By extension, such thickened oils also dry to tougher films, very resistant to atmospheric-attack/degradation when compared to 'raw' oils. In addition to water-resistance and increased durability against atmospheric-degradation, those particular thickened oils created through exposure to air and sun generally add a faster-drying activity to the resulting varnish. By comparison, physically boiling the oil to achieve 'body' tends to make it slower-drying. Keep this point in mind.

Paint

Paint can be made very simply. Paint is created when a binder is added to pigment. If egg yolk or glare is combined with colored pigments, egg-bound paint is formed. Egg yolk dries and hardens which 'glues' the pigment particles together and makes the 'egg-paint' rather durable. The olden Italian name for egg-bound paint is secco. Today most refer to it as simply 'egg tempera'. Hide glue or cherry-gum, or other plant-gums can also serve as pigment-binders. In the same fashion, common 'oil-paint' is made simply by mixing pigment with any oil which is capable of 'drying' , or, more correctly, solidifying. Such simple 'oil-paint' usually works quite well and pleasantly with a hog brush. You can brush it on and it pretty much stays where placed. Now, certain agents can be added to give the basic oil-and-pigment paint extra abilities. For instance, as simple oil-and-pigment paint is soft, slow-drying and sort of gummy --and can even be water-soluable -- adding an oil varnish to the simple paint makes that resulting paint tougher and more durable. Those are good things. The bad bit is that adding much thickened or bodied oils -- or even oil-resin varnishes --to the same simple oil-and-pigment paint gives that paint a tendency to slump and level just like typical enamel paint. In short, the resulting paint may lose its ability to keep its place when applied to a vertical support ... or to allow creation of upstanding highlights (impasto), which is a trait commonly observed in the old master works. In fact, the very worst-behaving "oil paint" can be made by mixing thickened/bodied oils or an oil resin varnish directly with the dry pigment. ...producing an awful slumpy stuff that wants to creep and run from its place in similar to asphaltum. Thus, whenever my own eyes behold an impasto-effect laid exquisitely upon the surface of an olden oil painting, I may fairly deduce something of its paint-make up. I will automatically suspect either the paint is made with simple raw un-treated oil, or that only a very small amount of thickened oil or oil-resin varnish was used in its make-up. Conversely, if the paint shows an enamel-like character, then I might easily suspect either a thickened oil or an oil varnish was added to the paint and in a goodly amount.

Ah, but there are certain ways and means to overcome my simple thinking, for as the common expression maintains, " things are not always as they appear".

Take Jan van Eyck's paint again, for an example. The best (for now) chemical analysis of his paint-binder matches that of an oil-and-pine varnish, and this would indicate he simply mixed his colored pigments with that oil-resin varnish, alone, as the sole binder. As already mentioned, I know from experience with handmade paint that such a paint should exhibit very bad behavior, in that it will not keep its place, oozing and slumping like enamel. Now, to a certain extent, Jan's paint does appear enamel-like in its smoothness; yet, here and there, the work shows-off a crispness that would not be attainable by use of a typical varnish-binder. Some painters have offered speculation that Jan resorted to an egg or egg-oil emulsion to create such crispness-- yet no traces of egg show in the most-up-to-date chemical-analysis. [For some examples and discussion of this egg-oil emulsion theory, see Frederick Taubes' "The Mastery of Oil Painting"; 1953; PP 13-27. Also, look up "Mische Technique".]

Incidently, history says van Eyck painted his amazing work by mixing his colours with a novel wonder varnish 'which dried in the shade' ... and, in Jan's case, our modern-day paint-chip analysis appears to corroborate that historical account. Yet, as noted, Jan's paint shows paint-attributes that often keep their perfect place and exhibit no slump; thus I must consider there was something very different about his varnish-invention -- something that set it apart from the commonly-used pine-and-oil varnish of his day -- which, again, was a typically slow-drying varnish and one that would have produced nothing more than slumpy enamel-like attributes when mixed with the various colored pigments.

As I mentined before: I find this very interesting; and also very curious ...for the Eyckian 'wonder varnish' -- and I am one who believes it was a varnish --does not seem to behave like an oil varnish would.

Above image: The relative clarity of ORIGIN (left) when compared to our mastic-based historical Bombelli Medium (on right). If ORIGIN is the sole binder for the pigments, the resulting paint will not noticeably yellow, as would inevitably happen if the same pigments were ground in simple oils. This trait makes ORIGIN unique as a paint-binder.

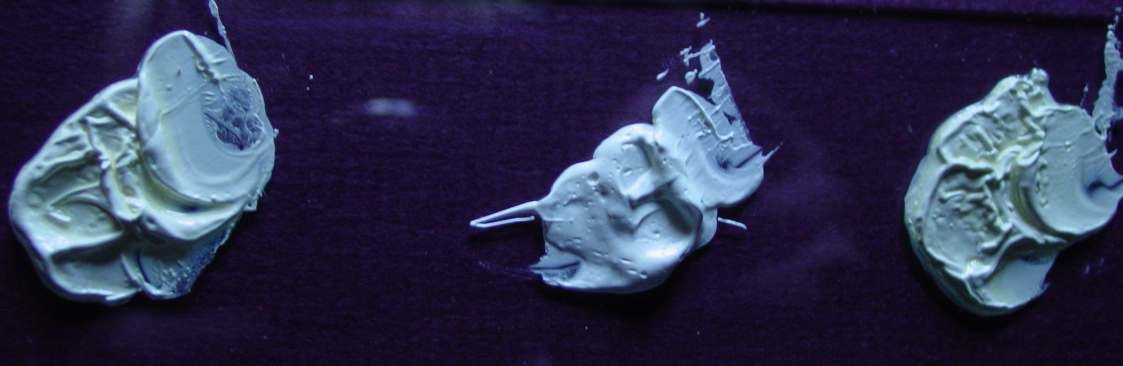

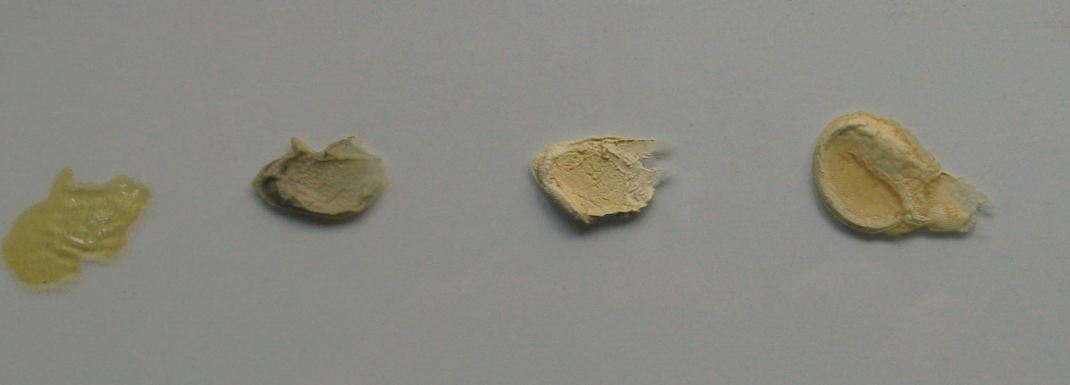

Above: ORIGIN is a traditional cooked resin-in-thickened-oil varnish which is at first a liquid; but then --soon after creation -- the varnish becomes congealed to a very firm state. This image demonstrates results in paint and character when ORIGIN is mixed with yellow ochre pigment: The left-side "slumpy" and enamel-like paint is created with the initial liquid-state ORIGIN varnish; while the right side (crisp paint) was created using ORIGIN varnish after it had congealed and became wax-like. As this image illustrates, a varnish which becomes congealed provides a "backbone" to the paint, allowing all sorts of effects, from impasto to washes, to very fine/thin lines, which hold their place and resist running/sagging/diffusion and trickling ('beading'). As such, ORIGIN solves the timeless problem oil painters encountered when grinding/mixing their pure pigments with either a thickened oil (stand oil, heat-polymerized or sun-thickened) or a pure oil varnish. While such paints are/were extremely durable, the semi-polymerized state of the oil-ingredient causes the paints to slump, creep, trickle, run with gravity. Such paint simply will not hold the brush-stroke as placed, even with solvent-use. This is another unique trait available only via the use of ORIGIN Congealed Varnish. [Note: If you have never made your own pigment-and-oil paint and use modern-day tube paints, instead, you will not be aware of this historical problem, as the congealed stabilizer in most commercially-produced oil paints generally overcomes the diffusion/creep/trickle effects typically engendered by the use of bodied oils or varnishes. In fact, many artists have come to actually appreciate the more-enamel-like effect of adding thickened oils or an oil varnish to their modern-day tube-paints.]

Above image: The same yellow ochre paints applied to a primed panel. The congealed varnish performs wonderfully compared to the uncongealed liquid varnish, which 'melts' and will not hold the stroke. Again, this is the exact same resin + heat-bodied oil varnish; first in its liquid state; and afterwards in its congealed state. The congealing character makes all the difference in paint-behavior.

As far as this painter/author has found, there are no recipes within the olden manuscripts/texts for making a congealed oil-resin varnish ...and neither is there such recipe for a congealed thickened oil. That stated, there does exist written reference as well as visual cues and examples which show that a varnish like ORIGIN did exist at one time, and was considered a great secret ...before it somehow became ...lost.

Uh-oh.... a "lost secret"?! Those oil painters who rebel at such notions, it is best you quit reading from this point.

Lost ways and means

I've always liked looking for lost things. Some folks like looking for rare coin and valuable metal. Myself, I enthusiastically stumble about with historical art materials such as pigment, oil and varnish, looking for the lost ways and means of great oil painting. I enjoy some fine company on my journey. I am walking with Joshua Reynolds, Julius Ibbetson, with Joseph Turner, with Merimee and Eastlake, Berger and Laurie ...even Jacques Maroger; and of course, you few other fools, out there. These earlier 'paint-detectives', you and I, we cannot agree on much; still we share a heady love and desire for the lost ways and means.

Some valuable tools have been missing ...missing from the oil painting craft for a very long time. As just one example, in Italy, strongly-gelling varnishes disappeared from oil painting-use around 1750. In the early-to-mid-19th C., certain landscape painters achieved amazing results using a weaker form of these earlier gelling varnishes, which in their turn also dropped from sight. Somehow tools become lost. Gelling varnishes have their place and some very fine artists today use them fondly. Still, I must relate most 'experienced' oil painters of today have no clue about these tools.

There are other valuable painting tools that have become lost.

Consider the cause undertaken by England's Joseph Turner: Some say his oil paintings look like watercolors, while his watercolors look like oil paintings. They do not; still I can understand the comparison. You see, Turner fondly painted in washes-- oil paints either bound with beer or gum, or meguilp, or wax, just so he could slightly or broadly wash-on his drawing and colors. He loved the light generated through transparent color. Turner traveled and explored the world. His eyes sought the wonders of the landscape while his mind struggled to find means for capturing that wonder with 2-D paint. Turner turned to the olden painters for clues to their own thin 'wash-y' ways and means. The Venetian painters of the 14-1500's were his ideal as to coloring (though Claude was his champion at design). Turner is not now able to defend his choice of tools but, as one of his admirers (Ruskin) noted, the means he found produced only fleeting brilliance, such that he would prepare his exhibited works in as fresh a state as possible, and this to allow the Royal Academy judges to see his work at its greatest brilliance, for to wait too many days would inevitably bring on a "painful deadness" so contrary to Turner's ideal.

The Venetian painters held an unknown ways and means to their coloring, one that remained lost and unavailable to Turner, and the multitudes of other painters standing in his shadow.

I might also mention the Pre-Raphaelite painters who found their own means for creating glowing color with mundane oil paint. Their use of a veil of stiff copal or amber-treated lean zinc white placed translucently over the careful drawing (so it might still be discerned through the veil), then overlayed tenderly with thin washes of color, produced an effect of illumination only seen in those aforementioned and much-older works. It was a tricky technique, and Hunt warned that any attempt to afterwards retouch those areas of glowing color resulted in the complete loss of that very effect. So that you might better follow along here, I will quote Hunt, as he 'spells it out' more clearly:

"...On the morning for the painting, with fresh white (from which all superfluous oil has been extracted by means of absorbent paper, and to which again a small drop of varnish [Copal or amber-JCG.] has been added, spread a further coat very evenly with a pallet knife over the part for the day's work, of such consistency that the drawing should faintly shew [sic] through. In some cases the thickened white may be applied to the forms needing brilliance, with a brush, by the aid of rectified spirits.Over this wet ground, the colour (transparent and semi-transparent) should be laid with light sable brushes, and the touches must be made so tenderly that the ground below shall not be worked up, yet so far enticed to blend with the superimposed tints as to correct the qualities of thinness and staininess, which over a dry ground transparent colours would inevitably exhibit. Painting of this kind cannot be retouched except with an entire loss of luminosity." [Holman Hunt, "Pre-Raphaeliteism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood", Volume I, page 276.]

This troublesome technique produced an odd intrinsic illumination within those sections of the painting where it was utilized. Comparatively dull colors like yellow ochre and Venetian red became 'lit-up' via this odd method, leading to a relative brightness not attainable through any opaque coloring.

Now, it should be noted that with the inventions of chemistry came a bright gamut of colored stuffs; and the resulting brighter and more intense pigments became available during the late 19th Century and beyond. Oil painters pretty much turned their backs on finding olden lost ways and means. Still, for some of us curiosity-seekers delving into musty texts, the historical examples of Turner and the PR-Brotherhood show plainly that oil painters have sought time and again to re-create the lost ways and means of producing intrinsic light and illumination with layered oil paint-- traits known and widely practiced during a much-earlier period of oil painting greatness ...then somehow phased out and lost. Of course, Turner and the PR-painters were not the only ones delving into such illuminating matters. In fact, there were many such fellow-wizards attempting the same ...and some achieved good results; but always by these same oil-y means-- means which will ultimately discolor and become yellowed ...or worse.

I have personally seen on numerous ocasions, modern-day research and illustrations claiming layered works can be built upon a white ground and retain that initial illumination through several over-applied transparent colorings, the light penetrating down through these several layers to the white ground, then bouncing back up through the whole, producing a wonderous overall illumination. Most claim this the very manner of the olden masters. This notion seems perfectly sane ...until one actually attempts the method ...whereupon the artist soon discovers that the bright illumination gleaned during his initial application of transparent/translucent color atop the white ground ....becomes lost when the second layer is applied. Try it for yourself. Things certainly glow with that initial layer; however, once that layer has dried and another color-layer is applied, the illumination dies straight away. At that point, you may as well resort to brighter opaque coloring, as your intrinsic illumination has been irrevocably lost; and this is exactly what Holman Hunt told us would happen.

In their attempts to recreate the lost manner, I would safely say that the Pre-Raphealite painters came the closest with their own novel but cumbersome method of gently painting thin tints atop wet stiffened white; but there is another way to achieve this same goal of producing paintings seemingly 'lit from within'.

Wait... what am I talking about? There are likely many reading my words and not comprehending my meaning. What I'm saying is this: If you look at an oil painting produced in this particular manner, that painting will exhibit an odd characteristic: If viewed in a dimly-lit room, the work merely appears as most any other; BUT, turn on the lights and the painting produces a weird sort of glow ... just as if there is a light behind the coloring. The colors suddenly jump into a stark brightness which causes any normal/usual/regular painting placed beside it to appear dull by comparison. Vasari mentioned that the wonder varnish of van Eyck, when mixed with the colors, produced an effect of brightness "as if lit from within". I think he was talking about this very effect, which comes not only through a proper binder but also the technique for its use. As for the actual technique involved, well, that rather resembles Hunt's and Millais' method, as well as a very old method used by the majority of painters back in the brothers van Eyck's day ...a time when nearly everyone painted using egg, glue or gum-tempera (egg yolk, hide glue, casein glue or, say, cherry gum as the binder for the colored pigments). I strongly believe it was this very visual phenomena of 'inner light' which created the late 1700's-into-1800's British search for the "Venetian Secret".

Rubens and van Eyck -- The Tie that Binds

In his 1830 book, "The Art of Painting in Oil...", J.F.L. Merimee mentioned that if a file were dressed over a painting by Jan van Eyck's hand, the surface of the paint took on the "shining appearance" of being painted with varnish*. Merimee stated another interesting tidbit. He claimed that P.P. Ruben's teacher, Otho Venius (AKA Otto Vaenius), painted with the original van Eyckian varnish and gave that device and the process for its use to his remarkably famous student (who, in his own turn, very likely handed that to his own remarkable student, Anthony Vandyke).** [*Page 14; **Page 18.]

I am uncertain where Merimee obtained this bit of info but I have never found any reason to doubt it.

According to the earliest historical word, both van Eyck and Rubens were said to have painted with varnish. In fact, there is an old mention that Rubens' critics claimed he painted with so much varnish that his paintings would not survive him. Adding to this, there are other obvious similarities in medium exhibited by the amazing works painted by each of these great craftsmen.

Aside from the historical word, modern-day chemical research generally supports Merimee's claim. Various paint-chip analyses of each painter's creations typically indicate a binder-composition of linseeed or wlanut oil "plus a little pine resin". In the case of van Eyck, the oil is "heat-bodied". Sometimes the oil in Rubens (and Vandyke's) paint is heat-bodied or heat-polymerized, and sometimes not*. ]*See, for example, The National Gallery Technical Bulletins regarding Rubens and Jan van Eyck.]

One particularly telling and notably uncommon characteristic is that the paintings created by van Eyck and Rubens dried with a gloss and required no additional varnishing at completion; and in fact, when cleaned of their aged and over-laid varnish coating/s --coating/s applied by caretakers/conservators down through the centuries --the original paint applied by these men can appear amazingly fresh ... and still exhibit their inherent gloss. I should interject here that this is a supremely amazing trait.

For supportive instance to this last notion, when the yellowed and degraded varnish was removed from Rubens "Samson and Delilah", instead of finding the usual matt paint-surface normally revealed by varnish-removal, the conservators found still-glossy paint. Conservator Joyce Plesters wrote: "As can be seen from his letters and from contracts, pictures often left Rubens' studio as soon as the paint was dry enough for them to be safely packed, so that it seems unlikely that they were as a rule varnished before they left the studio. In fact, though in his letters Rubens mentions the time taken for pictures to dry in connection with despatching them to clients, he never once mentions varnish or varnishing*. This does not of course exclude the possibility, or even the likelihood of their being varnished at a later date. It is noteworthy that when pictures by Rubens are cleaned, the surface after removal of old varnish often still retains a perceptible gloss, so that they could almost be rehung without revarnishing. By contrast most 'old master' paintings look matt and patchy in the unvarnished state. The 'Samson and Delilah' emerged from beneath the discoloured varnish looking almost like fresh oil paint." Plesters adds: " In the present state of knowledge it is not possible to say whether this special quality of Rubens' paint is due to the addition of some resin to the oil medium or to the mode of preparation of the oil itself", ( Plesters, National Gallery Technical Bulletin Volume 7, 1983; "Samson and Delilah": Rubens and the Art and Craft of Painting on Panel; Page 18). [* As regards Rubens never mentioning varnish or varnishing in his letters: He did, however, share a few words with Mayerne about that subject. Rubens told Mayerne that "the very best varnish is made with drying oil, much sunned with litharge and without boiling, at all". Rubens also mentioned adding varnish to his colors -- a practice I will explore later ...]

In light of this 1983 description of the cleaned-of-varnish yet 'fresh' and still visibly glossy paint, I pose a question: Has anyone reading this mixed pigment with raw or even thickened linseed or nut oil, applied that using a solvent, in layers, and had that painting dry with a gloss? Answer: No, it dries sunken, dull. It is possible to over-bind the pigment with thickened oil, thin that a titch with solvent; then apply it in a single layer. That should provide a gloss, yes; though odds are good the paint will slide down the support. Then again, one might wait months for an initail paint-layer to firmly cure before repeating the action. Yes, that might allow gloss-retention; but recall that Rubens was very quick at painting-execution, and that he utilized a layered technique in the performance thereof.

I believe this uncommon gloss-characteristic to be a particularly telling bit of evidence. When the old varnishes were removed, Rubens' paint retained a freshness... and a gloss. In my own experience, this rather singular and remarkable 'van Eykian characteristic' requires the use of a high-in-resin-content oil-varnish as the binder, whenever the work is built through multiple layers and with the use of a solvent -- which was the modus operandi of Rubens ... and quite possibly also that of Jan van Eyck. And I'll repeat, of all oil varnishes I've encountered, only a congealed version will allow the perfect capture of the stroke without subsequent slump or diffusion.

Following the Path...

The point I wish to persue here -- that the van Eyck brothers and Rubens may have used the same or similar varnish as the binder within their paint --is that it might serve in helping uncover the initial and wonderous van Eyckian 'lost ways and means' if we have other and later users of the similar or same device. The phrase, "the more the merrier", comes to mind; for if we can assemble the clues from the many it might better show the original path, which has become much hidden through the many intervening years.

Now, there are various ways to approach sleuthing like this; and I am one who prescribes the very best way is to take the historical word as truth and follow it as closely as possible; then to carefully 'watch' where it leads. I mention this because too many seekers of the van Eyckian ' lost ways and means' seem to take the historical word at the beginning of their golden trek ...but then head out in completely opposing directions.

Case in point: The number of researchers who have concluded the van Eyck brothers' discovery was simply another method of painting with egg, likely a combination of egg yolk and oil or varnish. Some call this egg/oil/varnish binder "tempera grassa". Unfortunately for those good souls pushing this particular painting technique, this very combination is mentioned by Vasari as having been tried, over-and-over, and always found wanting.

And so I should best not head off down that ravine, there; or over that cliff, yonder. I should stay on the vague path, as much as possible. Yes, I prefer to follow the path revealed and left to us all by the historical word; and really, why should I want to leave it?

In brief, the historical word initially begins with a famous/infamous story told by Georgio Vasari, some 100-years after Jan van Eyck had died. Essentially, Vasari claimed the following {and overlooking Jan's brother, Hubert, here}: Jan van Eyck was an egg tempera painter who, on one very notable occasion, varnished his dried egg tempera painting with the common varnish of his day. As this varnish was very slow to dry, van Eyck then placed his now varnish-coated egg tempera painting into the sunlight so that the oil varnish would soon cure --and I can vouch, this IS the effect of sunlight on common resin-in-oil varnishes. Unfortunately, the heat of the sun split the panel, ruining his great work. Seeing his loss, van Eyck vowed to create a varnish which would dry in the shade. He set about doing this and presently found his goal. He was pleased with his varnish invention and eventually decided to mix it with his colors, whereupon he soon found that he could paint in a sort of tempera-like manner, and that his paint possessed superior toughness, a saturation and "lit up" brightness of the colors ...plus an improved facility at blending (the ultimately desirable action of "melding" together under and over-layers of paint), as well as a wonderful gloss at the finish which obviated the need for a final varnish. All of these positive traits were there-to-fore unavailable to the near-universally-practiced egg tempera methodology, as well as the contemporanious means of oil painting (which, as the Italian craftsman Cennini recorded somewhat prior to that period, was a method of painting using either sun-thickened or heat-bodied oil combined with the pigments, or "colors"). Using his invention, Jan van Eyck began turning out works which were the complete envy of all the tempera painters who beheld them. [Note: Quoting Vasari from "Lives of the Architects, Painters, and Sculptors"; published 1550] "The mode of painting in tempera, which had been adopted by Cimabue from the Greeks about the year 1250, was followed by Giotto, and those succeeding masters who have hitherto occupied our attention; and it still continued to be the only method in use for paintings on wood and on cloth. The artists were, nevertheless, aware that pictures so executed were deficient in a certain softness, and in vivacity; and felt that, if a proper method could be discovered which would admit of blending the tints with greater facility, their works would be improved both in form and colour; the earlier practice (primarily using egg but also glue or gum tempera-JCG) having always been, to produce the requisite union of the tints by hatching with the point of the brush). But, although many had tried ingenious experiments with a view to such improvement, none had invented a satisfactory process; neither by using liquid varnish or other kinds of oils mixed with the tempera vehicles." [End quote] Vasari goes on to cite a few artists who tried combining egg with oils/varnishes: [Quote] "Among those who had in vain tried these or similar methods were Alesso Baldovinetti, Pesello and many others, but no works produced by them possessed the pleasing effect, and improved qualities which they sought; and, even if those artists had succeeded in their immediate object, they would still have been unable to give the same stability to paintings on wood which those executed on walls [such as was commonly done with (thickened) oil-bound paint] possessed. They could not, by such methods, render pictures proof against wet, so as to allow of their being washed without danger of removing the colour; nor was the surface so firm as to resist sudden shocks when the works were handled. These matters were often the subject of fruitless discussion when artists met together; and the same objects were proposed by many eminent painters in other countries besides Italy, in France, Spain, Germany, and elsewhere."[End quote] [Additional note: Regarding the aforementioned action of blending: Anyone who has tried egg-oil emulsion painting (AKA tempera grassa) will notice an increased ability to blend the paint during application; however, Vasari says combinations of egg and oil emulsions failed to improve the "blending of tints". Thus, I am one who greatly suspects that this sort of "blending" is not what the egg tempera painters desired within their craft. No. Instead, I believe they sought the ability to "meld" layers of applied and already "set" paint together --an ability I have personally found to be invaluable towards two-dimensional depictiion of three-dimensional reality. I'll repeat that this action of melding layers of applied paint cannot be obtained either through regular oil painting, egg painting, or combinations of the two systems (AKA emulsions or so-called "tempera grassa"). Also note: If interested, you can find a decent translation of Vasari's story regarding "Johannes of Bruges" (Jan van Eyck) and Antonella da Messina in Eastlake's first volume, "Materials for a History of Oil Painting; pages 201+". Do find it using google books, and read it several times.]

The gist of Vasari's account is Jan discovered a method of painting in oils that resembled but improved upon the then-universally-preferred tempera METHOD ...but instead of egg or glue, or gum, Vasari tells us that Jan used his "varnish that dried in the shade" as the pigment-binder. [Again, from Vasari, quoting that author: "(van Eyck) ...began to devise means for preparing a kind of varnish which should dry in the shade, so as to avoid [the danger incurred by] placing his pictures in the sun. Having made experiments with many things, both pure and mixed together, he at last found that linseed oil and nut oil, among the many which he had tested, were more drying than all the rest. These [oils], therefore, boiled with other mixtures of his, made him the varnish which he, nay, which all the painters of the world, had long desired. Continuing his experiments with many other things, he saw that the immixture of the colours with these kinds of oils [Vasari must rather mean the invented varnish here, and not the oil] gave them a very firm consistence, which, when dry, was proof against wet; and, moreover, that the vehicle lit up the colours so powerfully, [and] that it gave a gloss of itself without [the need to have a final] varnish; and that which appeared to him still more admirable was that it allowed of blending [melding the paint-layers] infinitely better than [egg] tempera." [End quote] [Note: Please pardon my inserted words sprinkled within the quotes of Vasari. It should be considered that Vasari wrote in troublesome-to-translate old Italian. His story about "Johannes" arrived via correspondence with other artists and with the Flemish ministry. Vasari was a practicing oil painter of the simplest means. By his own testimony, Vasari did not use solvents nor varnish; and he was, himself, admittedly and rather blissfully unaware of any other method of making oil paint beyond that basic of mixing raw or thickened oil with his colors (pigments)-- a method that will produce somewhat lasting works in a clime such as predominantly sunny/dry Italy, but eventually invite decay in damp/cold realms, such as Northern Europe. For Vasari's own direction as to how oil paintings shall be constructed, see my notes and his quotes near the end of my info-page on "Bombelli".]

I especially call your attention to the above underlined passages, "gave the colors a very firm consistence" and "lit up the colors so powerfully". Neither of these particular traits can occur using either a liquid varnish or a thickened oil. No, these traits come via suspension of the pigments-- meaning the varnish must have been congealed. This trait I have suitably demonstrated in those prior images using the pigment yellow ochre. Again, those painters who use modern-day tube paints containing a congealed stabilizer cannot or will not grasp this basic historical paint-phenomenae; and I'll presume neither will those reading this who have little or no experience making then painting with all the traditional oil-varnishes or thickened oils.

Now, some historians offer evidence showing Vasari's story was suspect on this or that ground when compared to recorded history, and so be it; but as regards to the actual invention by van Eyck, no one offers anything truly valid against that matter; and it turns out there were other well-known painters who were provided the 'invention' and apparently these one-time egg tempera painters were also able to reproduce van Eyck's workmanship. As these other painters works seem to show the same unusual characteristics as van Eyck's work, it necessarily becomes a bit tougher to ignore the whole historical scenario. Oh, sure, one can ask about brother Hubert's role in the discovery, but that matters not towards the 'invention' and its extraordinary attributes.

Rubens again...

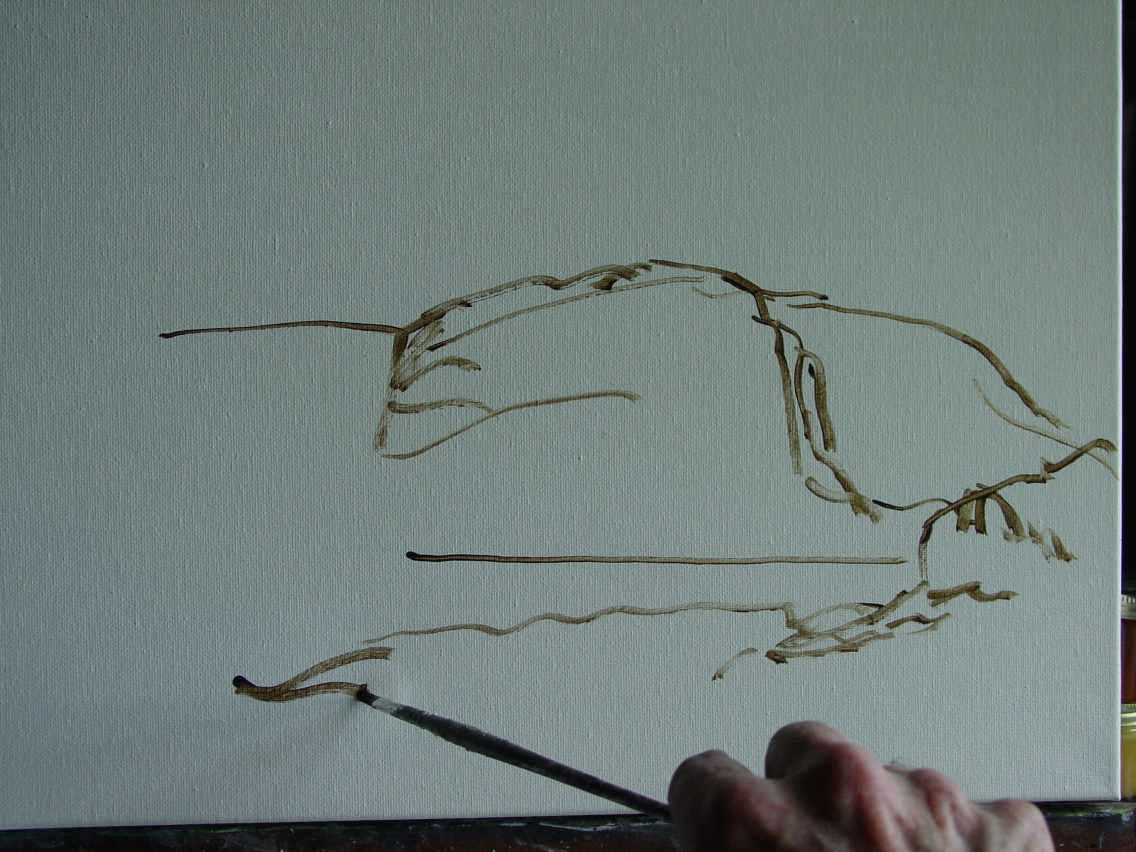

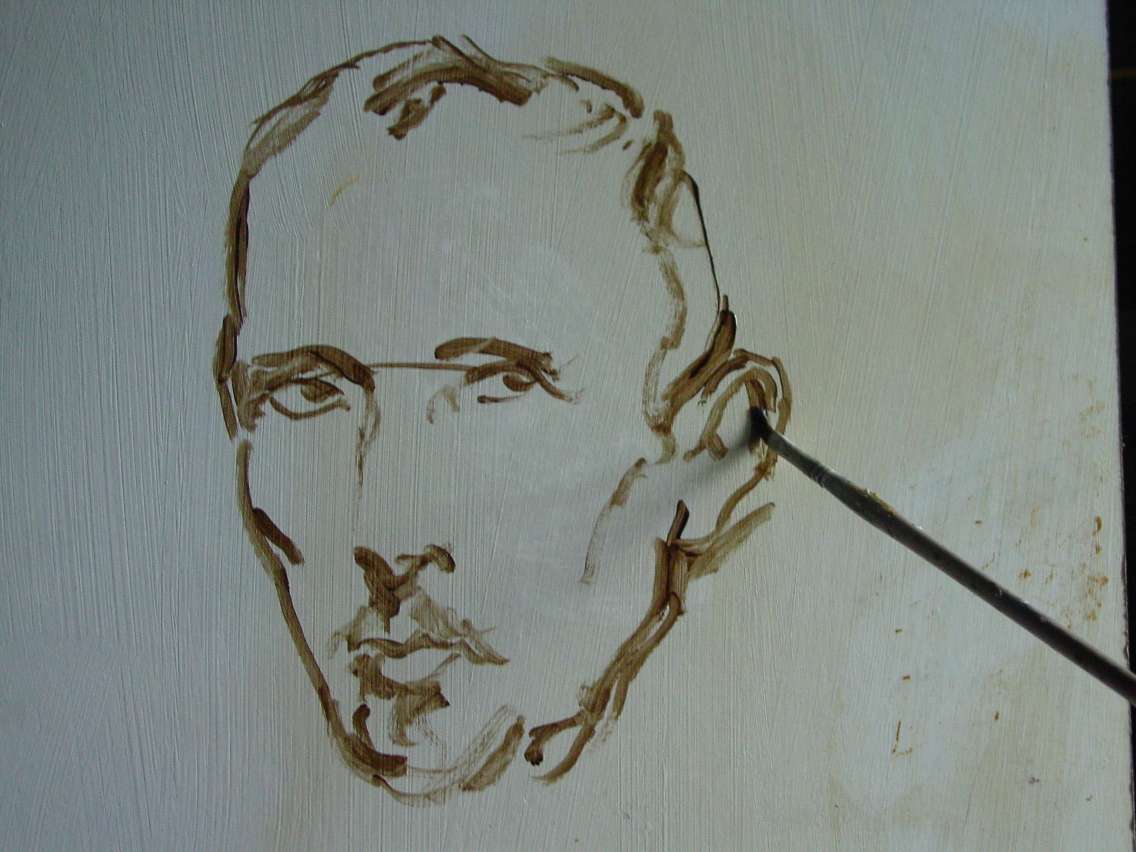

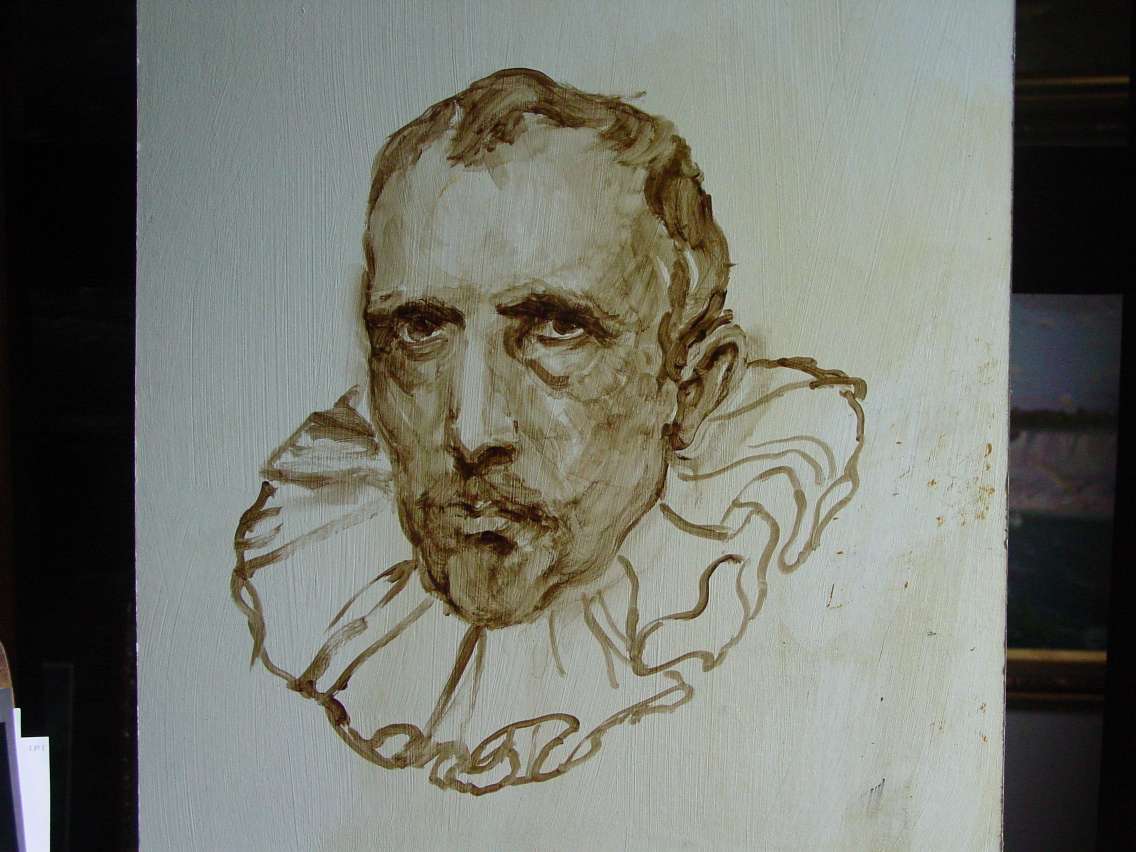

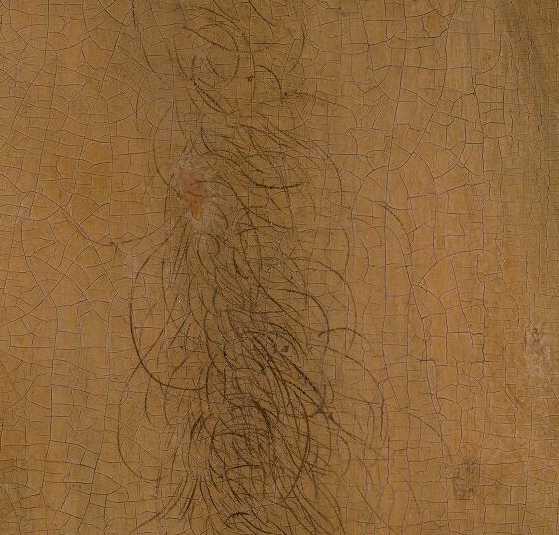

The detail above from a study for "The Lion Hunt" shows the "cartoon" or preliminary drawing typical to Rubens' method. Here we see Rubens use of a brown with the visual attributes coresponding to asphaltum. The transparent brown is of the apparent consistence of an ink-like wash. The darker lines are delineations, while the lighter weaker browns are used as shading. I surmise that Rubens has dosed this brown with a lot of turpentine; yet the brown steadfastly remains where placed, even when thinned-down ever more for the shading. There is a faint indication of spreading but there is no running. This enigmatic clue indicates -- strongly -- that Rubens gave this brown an addition of some sort of binder which possessed a strongly-congealing property. Also, very telling, notice how Rubens has stroked shading over previously drawn delineation-lines (the "S" line) and yet that initial line does not spread or disperse when over-drawn. This indicates Rubens' brown is setting very quickly, just as spirit-based asphaltum does. An actual oil paint will never allow this same ability; that is, unless it is allowed to dry first.

Here is another example of Rubens' drawing, this time from another study, "The Meeting of King Ferdinand..." (J.Paul Getty Museum). Also, observe the white lead paint used to indicate hair. That paint is granular and torn, which are strong visual indicators Rubens' white lead paint was congealed at the time of application.

Another detail from "King Ferdinand": Again, easily discerned beneath the transparent over-paint is that now familiar brown under-drawing, washed-on thinly via the use of a solvent; and very likely gum turpentine-spirit, as, by his own words, Rubens considered that his favorite to oil of spike.

Getting back to Rubens: While painting Doctor Theodore de Mayerne's portrait, Rubens told the physician that the "colours" (pigments) should be made ready by mixing them with solvent. Rubens said he preferred using that solvent we know today as gum spirits of turpentine. [Mayerne: "Sir Peter Paul Rubens said that all colors should be ready-ground, employing for this purpose spirit of turpentine*, which is better than spike oil and not so strong" (*Eastlake; "Materials...",Vol. 1, page 529). Rubens actually said "the essential oil of Venetian Turpentine which exudes from the larch-tree, and distilled in a water bath", which would be an exceedingly pure form of what we today call "gum spirits of turpentine". For my enlightening research into the exact nature of Rubens' turpentine solvent, go

here.]

Now a question: Why would a painter begin by 'moistening' or grinding his dry pigment with a solvent? For too many years, Rubens' odd direction to Mayerne confused this author -- and so many others; but, then again, we current moderns have only known one generally-understood manner for constructing oil paint, which is that our colored pigments are first "ground" (dispersed, or as an even better descript, rubbed-up) with a limpid drying oil --usually either walnut, poppy, hemp, or linseed --before anything as regards actual painting takes place. But what if the binder some earlier painters used was not simply a liquid and fluid oil? What if that binder was so very thick that it could not be mixed directly with the dry colors?

I believe to truly understand what Rubens meant by his odd direction, one has to become aware of unusual -- dare I say "lost" -- ways and means.

In this curious cause, and central to any further understanding, one should consider what agent bound Rubens paint. A solvent is not a binder as it evaporates. Spirits of turpentine contains a faint amout of pine resin but far, far less than would be essential to holding pigment together. By comparison, fixed oils, especially drying oils -- such as linseed or walnut-- do not but barely evaporate; and so they become a sort of semi-solid 'glue' that does hold the pigment together. Thus, oils that dry would certainly 'bind' the pigments ... but what else? What other 'binders' were available to Rubens, historically?

To narrow the multiple choices, I should mention here, modern-day scientific analysis discloses that Rubens' paints were bound with either walnut or linseed oils, as well as a "faint amount of pine resin". Now, consider, if Rubens' paint was to be bound with a simple oil -- or even, say, an oil coupled with some pine-type balsam -- then why would he need to 'pre-wet' that pigment with a solvent, for as anyone who makes their own paint will know, raw or even thickened oil (with or without a balsam) mixes rather easily with dry pigment. And so I am one who must believe that the binder for Rubens' paint must have been something stronger, such as a cooked combination of oil with a resin-- a combination otherwise known as an oil varnish, or, more precisely, an 'oil-resin varnish'. Further, this oil-and-resin varnish must have been either very thick ...or congealed.

This plausible scenario --that of using an actual varnish-binder-instead-of-oil -- did not take much reasoning on my part, for Rubens actually tipped me off when he described such a binder elsewhere in Mayerne's text. He mentioned adding a "hard varnish" to his color/s : Mayerne Manuscript; Rubens: "To use smalt so that it shall be beautiful and light, it is necessary to temper it with the hard varnish: then lay it on smoothly and do not work it too long, because over-working spoils the color: but when dry it may be worked upon to suit. The same mode may be adopted for blue bice. Ultramarine and ultramarine ashes are excellent for finishing the distance"..

There you have it. Rubens' told Mayerne that he (Rubens) mixed a varnish with his colors-- in this particular case he mentions only blues (smalt, blue bice, and Rubens compounds his direction by also mentioning two other pigs: ultramarine and a grey, which by either conjunction or simple 'slip of the tongue' seem meant for the same treatment/varnish-addition). A stretch to deduce? Well, something else to consider: It is precarious craftsmanship to add a certain binding agent to one color while avoiding that same or very similar treatment with others. For example, the use of a strong binder (oil varnish) in blue while using a weaker binder (say, just oil) in the other colors will cause differing stresses between and within the paint-film/s, resulting in eventual cracking/delamination problems. Know that Ruben's tough paint shows a uniformity of surface. There is nothing unusual or visibly apparent to indicate that Rubens utilized differing binders. Thus we can fairly assume that if the master added a varnish to his blues, he very likely added that same varnish to all his pigments. [Stability: When painting in layers, it is paramount that certain rules be followed. You are probably aware of the principal of "fat over lean"? Rubens --and the Van Eycks -- painted in layers. More than a decade has passed since I put forth the notion that a layered painting should best be accomplished by applying more-flexible layers of paint on top of less-flexible layers of paint. You see, I realized that the various notions of properly layering paint, i.e., "fat-over-lean", "soft-over-hard", "thick-over-thin", "slow-drying-over-fast-drying", etc., could all be combined then summed-up nicely by the simple phrase "more-flexible-over-less-flexible". The concept of "same-over-same" also fits this phrase owing to the initial layer, having dried or set, allows the same binder in the same amount to be applied safely --the fresh layer being more flexible than the dried or "set" layer beneath it (the concept of "more-flexible-over-less-flexible" has since been grabbed-up by several paint-maker's/painting gurus and has spread throughout the web). Again, it's all about stability! Painting in layers requires stability and for that you follow the encompassing rule: more-flexible-over-less-flexible. Now, as one glaring example which pertains, if you place a resin-in-oil varnish atop a paint-layer that was bound in heat-bodied oil, you will eventually experience cracking in the resin-in-oil varnish coating. The reason for this is the resin-in-oil varnish becomes harder and more brittle --less-flexible --sooner than the heat-bodied oil layer below it. Because instability within paint-layers leads to visually apparent faults such as cracking or fissuring, knowing this simple rule can also allow the painting sleuth to infer certain things about the binding media in an olden work. For one example, if the modern day paint-chemist/conservator finds a layer of resin-in-oil varnish sandwiched between two paint-layers and there is no instability issues (no abnormal cracking or other fault), then it is almost a certainty those two paint-layers are also bound with the very same resin-in-oil varnish. Now, as often happens, that same resin-in-oil binder may not even show within a chip taken from either paint-layer. Why? Realize, it is more difficult to detect the accurate make-up of a binder within a paint than within a pure unpigmented film. As one reason, pigment takes up space and so the binder-element is less. Pigment also hides fluorescence, which is another detection clue inferring resin-use. Thus, the fairest analysis and detection of a binder's make-up will come from either pure un-pigmented coatings, or binder-rich glazes, which contain less pigment. And yes, I am aware of modern day chemist's odd findings of additions of egg-here and gum-there in various sample-chips taken from old oil-painted masterworks. It certainly happens; but I would suspect and suggest the hand of earlier-restoration as causal to most such findings. Early and later-day restorers use/used anything and everything in their attempts to mimic a master's touch-- see Julius C. Ibbetson's "An Accidence of Gamut of Painting in Oils", 1879: 1828 edition available through Googlebooks.]

My myopic eyes eventually focused on something else: By Rubens' description to Mayerne, the word "hard" is coupled with the word "varnish"; and so I must wonder, what did Rubens mean by his mention of a "hard varnish"? Was this a varnish composed of oil and a "hard" resin, such as amber or copal or sandarac? Certainly, within the 19th Century, a "hard varnish" was indeed composed of thickened oil and such hard resins as copal and amber. But, curiously, the descriptive "hard resin" is not found in the written word from that much earlier time-period. Resins were simply resins (though there was some distinction in the color of the final resulting varnish, i.e., dark, red, light). Myself, I would accept the rather obvious and simply deduce that Rubens meant the term "hard" or "firm" to be an adjective, or the actual physical state of his varnish; and very likely meaning the varnish was a "solid" as opposed to a "liquid". Some might think I stray afield here, but besides being a painter I am, again, also a varnish maker, and I have experienced many odd findings within my field. Four-years ago I revealed the existance of these congealed coniferous varnishes-- varnishes I term "S-P-F (Spruce-Pine-Fir) congealed varnishes". These congealed varnishes do exist and they could easily pre-date mastic-based meguilp 'jellies' which gained such affection within the later 1700's. And so, yes, please think of this possibility for a "hard varnish": A solid varnish. Understand, I am privy to an insider's point of view in this matter. Again, these congealed varnishes exist. It is not a broad jump to allow the possibility that Rubens may very well have been referring to a congealed coniferous oil varnish; and also understand the generally -- and 'scientifically' --accepted ingredients of oil and pine resin within Rubens' paint lend plausible credence to just such notion.

If anyone is still reading along here, I should point out that these coniferous congealed varnishes --being almost as stiff as wax --are very difficult to incorporate with dry pigments. Thus, the initial wetting of the dry pigment with a solvent proves to be an expedient practice. I should also add, by the way, this practice would exactly mimic the wetting of dry pigments with water before incorporating the also-congealing egg yolk, as in the method of secco-- or egg tempera. You see, the original egg tempera practice called for using water to initially wet the colored pigments; then a bit of congealed egg yolk was intermixed with those wet colors, producing a gummy paint and requiring the brush be dipped and saturated in water, then stropped upon and throughout the stiff egg-bound paint in order to carry that wash of color to the panel. The technique of egg tempera painting primarily involves the laying-on of color in thin washes. The washes "set" through the action of evaporation and the congealing action of the yolk-binder, allowing further thin washes to be applied gently, delicately, until the artist is satisfied. Realize, this tempera technique of painting on panel was well-known and practiced by the van Eyckes; and it would be no great leap in deduction to conclude that egg tempera painters would seek to incorporate the very same technique .... with oil paint ...were there a ways-and-means found to do so.

ORIGIN VS Fir Wax

And so, as with egg tempera, ORIGIN-- a congealed coniferous oil-based varnish -- requires the use of dry pigments coupled with a "wetting" agent -- a solvent. This is an important distinction between Fir Wax and ORIGIN. Fir Wax was formulated for use with oil paints already "ground" using oil as the binder; however, like with egg yolk, ORIGIN is used as the actual and sole binder. If ORIGIN is mixed with regular handmade or most commercial tubed oil paints, the resulting paint behaves in similar to using a mastic-megilp: It keeps its place nicely, as a fine "jelly medium" would. But this is not the intended manner of utilizing ORIGIN. The preferred manner is that of using a solvent and developing the painting using a tempera-like delivery :Multiple thin washes but also thick impasto when called for....and all with the added convenience of a blending 'window of opportunity' (which is typically several minutes if using a mix of turps and mineral spirits). This system may have been the "tempera manner" of applying oils alluded to by Vandyke in his small manuscript, ""Observation of Anthony van Dykii", published just before his death; and apparently, this was also Vandyck's own usual painting technique, for he cited opinion that this "tempera manner" produced the best results. [Vandyke: "The tempera painters whose manner of applying the tempera technique was reflected in the way they handled techniques in oil, were the best.", "Observation..."; Introductory Page.]

I have little doubt that Vandyke obtained his own painting method through a study with his master, Rubens.* 4-years have elapsed since my public introduction of Fir Wax, wherein I also ventured the notion that Rubens utilized a congealed oil-and-coniferous-resin varnish with his paint; applying that same paint using a solvent, just as if he were painting in an 'egg-tempera-like' manner. In the interim I have found no reason to retract this position. I will say something more: Fir Wax was made using sun-bodied nut oil and fir resin cooked to a certain temperature and only high enough to combine the resin with the oil-- though not enough to completely destroy the resin's "markers"; and this heating act possibly allowing for a faintly-detectable finding of "pine resin" in Rubens' conjured paints. You see, to incorporate most coniferous or pine-like resins with a thickened oil, it is not necessary to cook the varnish to nearly as high a temperature as, say, amber or copal would require. [Be it known, cooking amber and copal and sandarac resins in oil to those amazingly high degrees does necessarily annihilate the amber or copal or sandarac-markers. Duly note that this is an established-by-'science' factual happenstance.]

ORIGIN is a congealed oil-and pine varnish "that dries in the shade". Thinned with a solvent, ORIGIN makes a perfect final-protective coating for oil paintings; or as a sealing or imprimitur coating atop any priming. ORIGIN is made using heat-polymerized nut oil and a coniferous resin common to Northern Europe. I should again mention -- and it has been fairly-well established by 'science' -- that a heat-polymerized oil containing faint amounts of pine resin has been detected in the brothers Van Eyck's paint. For example, see here again: and carefully note the last part mentioning the well-preserved clear varnish coating of heat-bodied oil-and-pine resin on the back of the panel matches that very wonderous binder found within the van Eyck paint. And so, based upon the latest analysis, the van Eyckian pigment-binder is/was very likely a resin-oil varnish.

Repeating myself, this most recent finding of science should not surprise anyone familiar with the varnish-making of that long-ago time, as thickened oils -- either created through sun-exposure or by boiling-- were regarded as the much-better oils to cook with the resins. This typical practice produced the toughest varnishes; and so this 'finding' easily equates to the brothers using a pine-resin-in-oil varnish as their paint-binder ...which rather neatly follows the original story penned by Vasari and concerning Jan's discovery of a wonder varnish 'which dried in the shade'.

To avoid confusion, be mindful that FIR WAX was/is a congealed oil and resin varnish conjured using a resin and a sun-thickened oil. ORIGIN is made using a coniferous resin and a heat-bodied oil. Why the difference? Well, Rubens told Mayerne that the best varnish was made using oil much-sunned with a lead-oxide and without cooking, at all*; and so I felt it best to follow Rubens own direction as closely as possible when constructing the congealed varnish -- a varnish I figured he would most likely utilize. This varnish would certainly dry his paints quickly. However, I know from experience that sunned oils tend to yellow sooner and greatly. As many years of trials now have shown me, heat-bodied nut oil will yellow only very faintly with age; thus I must deem the ingredient of heat-polymerized walnut oil to be the better oil for this congealed varnish. The resulting congealed varnish is somewhat slower to physically 'dry' (solidify) ... but that effect provides the opportunity to lay on many, many layers before final solidification of the applied paint occurs. There is a certain ease and freedom with this type of system. The painting can be built-up in a single day or it can be wrought over several days; but, in the end, the paint dries throughout, as if a single layer or "alla prima" technique was performed. This means the actual paint will not only resist yellowing and dulling, but also fissuring and delamination -- faults that would normally occur with the increasing vogue for applying straight and simple oil paint in numerous layers -- a dangerous practice straying from the rules of sound craftsmanship. Also, very importantly, an overall "lit from within" illumination can be maintained through this re-layering-while-wet methodology. [*Note From the Mayerne Manuscript: M. Rubens NB; "Turpentine (coniferous balsam, alone) in time becomes arid (oxidized) and is not proof against water. The best varnish, resisting water, is made with drying oil, much thickened in the sun on litharge, without boiling at all." I have underlined the word "with" because Rubens means the varnish will be composed of both the lithage-treated sun-thickened oil AND the balsam, combined together, and this act likely performed through a basic heating-process. The inherently yellowing-nature of the sunned-oil ingredient --either linseed or walnut oil-- within the varnish was apparently not a major concern to Rubens; or perhaps he was unaware of the essentially non-yellowing nature of a decent heat-polymerized oil.]

I should mention that, like Fir Wax, ORIGIN performs well with certain and generally considered nefarious olden pigments, such as asphaltum.

Colors

A basic set of dry pigments capable of handling a variety of subject matter would be the following (and I can recommend RGH online for ordering dry pigments that are not 'gritty'). Excepting the white, if you are new to making your own paints, order your color-pigments and black in the smallest increments offered. As for your white, that pigment should be ordered in larger amounts.

Lead, or Zinc, or titanium whites (with this system of coloring, it doesn't matter which, though I'll heartily endorse the most opaque zinc oxide for this method -- my reasoning will be submitted near the end of this essay)

Lamp black

Yellow ochre

Cad yellow medium or light

Iron Oxide red, such as Venetian Red

Vermillion or Cad red medium

Ultramarine blue

Prussian blue

Asphaltum (Gilsonite): Certainly not necessary but many early masters did use it. It does have unique qualities. Thomas Moran couldn't do without it..

Note: Western Maryland Gallery now offers these same artist's permanent pigments (excepting asphaltum) in a 'starter' 8-color set at $48.50 per set (Note: Pigments not sold individually). More info click here

Demonstrations

To give an idea of the general use for this congealed varnish, I'll submit a following step-by-step demo. But first, a few words about creating the actual paint bound with ORIGIN.

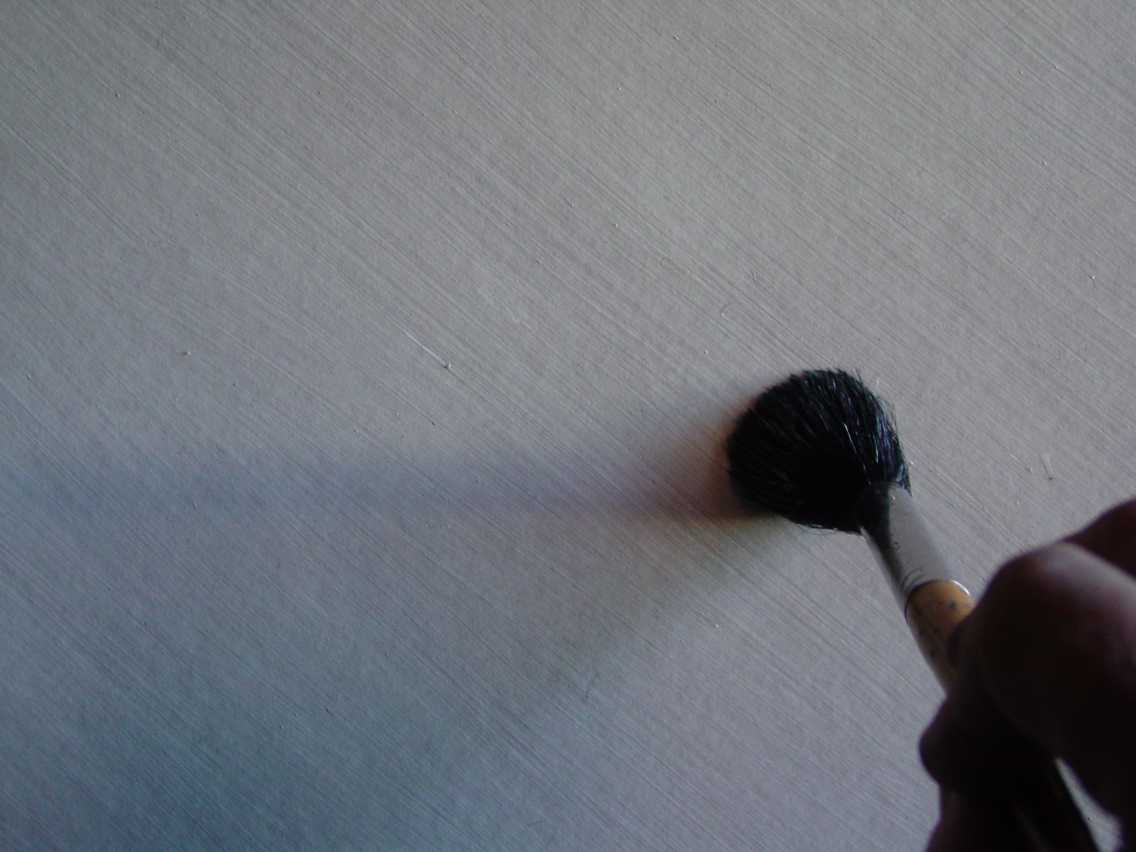

In most every case --excepting white and asphaltum -- a small amount of dry pigment (about a garden pea's worth) is placed upon the palette. A few drops of solvent are added to "moisten" the pigment and work it up to a paste with the knife ...like so:

Then an amount of ORIGIN Congealed Varnish approximately equal to the white paste is mixed in using the knife. The amounts of ORIGIN is typically increased with the various colors. [Adding more ORIGIN increases transparency as well as the paint's resistance to solvent-attack; though always bear in mind that too much oil in a thickly-applied paint results in gumminess. The general rule with ORIGIN and all oil-based binders shall be that medium-rich paint must always be applied thinly to avoid gumminess.]

You rub the paste and ORIGIN together and the paint is created, as so (next 2-images).

Hopefully, this appears as simple as it is. There's no mulling; everything is done using pigment, solvent, ORIGIN, and your palette knife. You see, if the pigment you obtained is truly pigment, then there is no need for further "grinding" or mulling of that pigment. The only act necessary to creating your paint is that of dispersion of the pigment into the solvent and binder (ORIGIN).

For my white (shown above) an amount of zinc pigment (yes, zinc is just dandy) equal to a marble was used and the amount of ORIGIN was a little more than half-that (though much more can be used). As for my asphaltum -- which I utilized for this particular demo because it was a favorite with this olden technique -- that lovely brown resin was previously melted into mineral spirits and so I merely scooped a pea's-worth from its container then mixed that paste with an equal amount of ORIGIN (yes indeed, the notorious asphaltum was used for my monochrome sketch and you will find much more info about this wonderful ancient color further along on this page. Asphaltum is not the n'er-do-well as so-often claimed). I usually work-up my initial colors and white rather stiffly, which comes in handy for impasto-work, but stiff paint is not useful at all for washing-in the drawing or the first colorings; thus I thin my asphaltum quite a bit with my mineral spirits. The thinned brown color glides off the Taklon and sable brushes which I prefer for this technique. I'm using a commercially-prepared 16"X20" canvas. Important! I have sealed the somewhat porous commercially-applied priming by having previously given that a thin coating of drying oil, made using nut oil, turps, and some varnish ...plus a few drops of siccative de Courtrai -- and which dried overnight. Solvent-thinned ORIGIN can also be used for this purpose. This clear sealing coat takes the place of a tinted imprimitur, which makes the technique go better than were it not applied beforehand, as there is less noticeable solvent-attack on set under-layers when applying fresh over-paint.. I should also mention that at no part of the painting process is there ever a need for oiling-out or lubricating the ground; nor do you 'paint into a couche'.

Delineating then washing-in the monochrome. This is simply a made-up design. Frederick Church once recommended that an artist should grasp the essentials of nature in one hand, then do as he/she wished with the other. I'll follow his advice with this painting of an imaginary landscape. By-the-by, in contrast with Holman Hunt's advice, I am beginning this little work in the late afternoon.

Below: The asphaltum sets quickly, allowing the first delineation lines to plainly show through the subsequent and even thinner brown shading of form.

Do you notice the similarity between my preliminary washed-on drawing when compared to those examples by Rubens, shown above? You should; and even though my canvas presents an obvious weave whereas Rubens' examples were sketched on smooth gesso. My asphaltum brown wash amazingly stays where I place it -- an amazing feat when one is cognizant of the inherent tendencies of true asphaltum.

Next Image: The general sky begins about twenty minutes later. The asphaltum has set and will be resistant to overpainting. I mix-up some ultramarine blue paint then add it to some of my zinc white to form a lovely bright blue. Zinc white makes such 'pure' light blues-- like Hunt, I generally favor it over lead white; and a mix of the two is just dandy. Thinning the paint with solvent and using a bigger brush allows me to wash-in the sky in a translucent fashion. My much-preferred brushes are soft filberts or "rounds". I drag some pure white into the blue-sky to approximate the effect of descending rays of noon sunlight, blending the sky together well....and quickly, for ORIGIN-bound paint "sets" with the evaporation of the solvent (I'm using a mix of turps and mineral spirits) ...and once it sets, there can be no further blending... unless the brush is lightly 'wet' with solvent again and the whole area gently stroked ober. Judging from Rubens' mention to Mayerne, smalt, applied pure as a blue glaze (being too weak to be mixed with white) may have become "set" too quickly and appeared "stain-y", thus being especially troublesome to achievment of an overall even gradation.

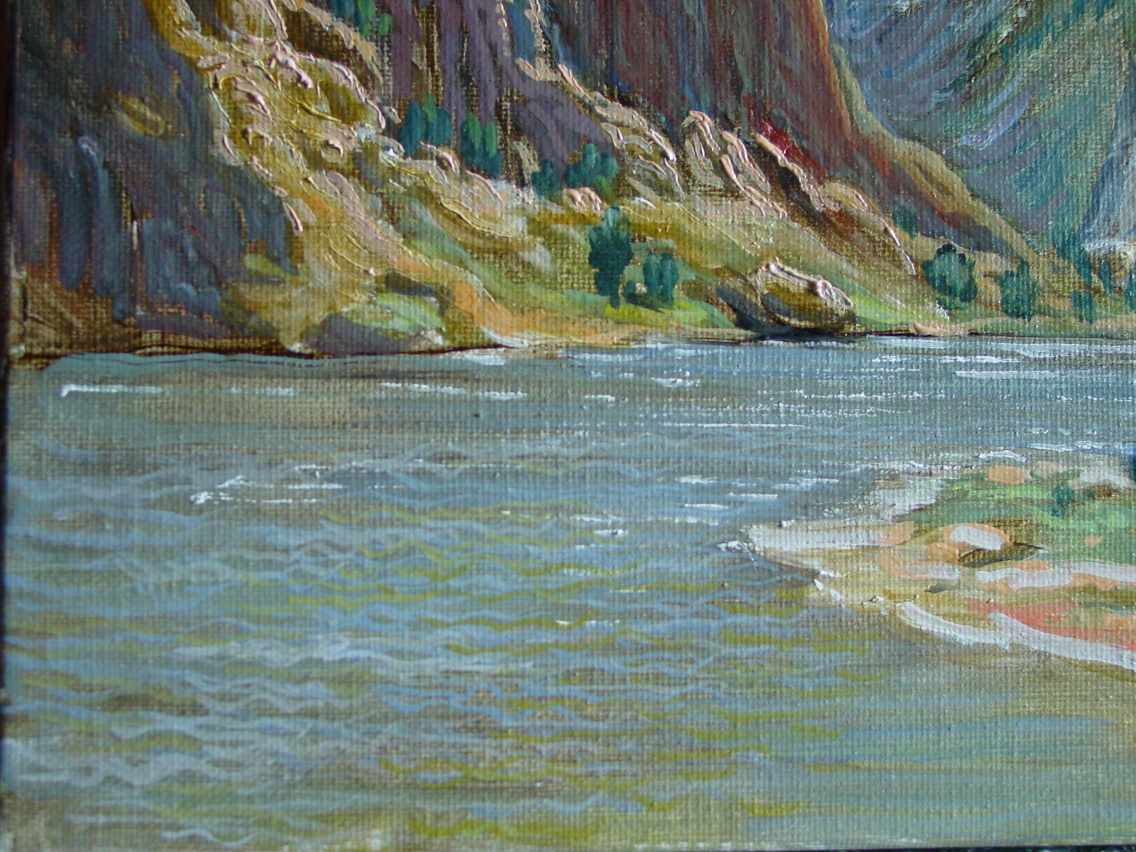

Below: The first washes of color were applied transluently to the distant mountains. As there are no green pigments in my arsenal, I used a few similar greens and shadows composed of cadmium yellow, yellow ochre, ultramarine, a teensy bit of iron red, and a bit of white for atmospherics, dipping my brush in solvent then stropping it back into my too-stiff ORIGIN-bound paint to create translucent washes, which are applied with facile brushstrokes generally following the contour of the hillsides.The practice is very much like watercoloring. I hunch Turner would be pleased ...for paintings composed with ORIGIN --unlike wax -- do not lose their freshness within days of creation.

It began to get dark as evening came on but I did not adjust my camera. As with Hunt's example, most painters would never begin a work near the end of day but this tempera-like technique suffers nought from such practice. Everything about the application will be freely available on the morrow, or even the day after --excepting I will be making more white each day on my palette. If I fail, from time-to-time, to add solvent to my white and re-mix, it will become quite firm right on my palette. I need my white soft and facile for initial modeling. As it thickens with evaporation of solvent on my palette, my white becomes stiffer and can then be utilized for rugged or sharper highlights/texture. The other colors will be treated as if they were hardened cakes of watercolor, the solvent-wet sable brushes stropped across each to refresh and become charged with the color. Remember, most coloring is applied in transparent or translucent washes. Of course, if I need some pastose COLORED paint for some desired vigorous display, well, that is quickly conjured fresh; still, mostly I'll use washes of color atop my design. Below image shows my placing of pure thicker white highlights here-and-there over shadow and mid-tone blue and other color-greys. These white "heightenings" will be later subdued by various solvent-thinned color-washes (i.e., glazes/scumbles).

What follows is a close-up larger than life-size showing the original asphaltum monochrome showing through the transparent/translucent local color and shadow-washes. Impasto is only applied in the highlights -- and I've just washed-on a glaze of yellow ochre atop the now-set rock-highlights on the left. Heightening then glazing/scumbling can create amazing illumination and textural effects. This feat is very quickly accomplished using ORIGIN bound paint -- it would take days or weeks to do the same with regular oil paint.

Below view: I've now washed a mid-blue-grey over the distant heightenings; and also washed local colors over my foreground. Some foreground colors are pure while others have a titch of white added.

Above and below images: Purer greens come from a mix of cad yellow and ultramarine ...and especially Prussian blue, which is a "greener" blue. The initial brown for my tree trunks is lamp black with a touch of iron oxide red. I perceive this brown often in my surrounding environs. I abhor umber in my own work. Note that I have used a wash of my leaf-green shadow tint to apply a shadow of a passing cloud opon my distant central hillside. If too pure, wait for that to set then wash-over a bit of blue-grey, causing the shadow to become faint and recede into the distance

Following image: The light was fading fast. Time to give it up. The paint will set-up more firmly overnight. It's not close to being dry, though, so any new layers added tomorrow or the next day will not thwart the overall and intrinsic 'alla prima' character of the actual paint. Every layer added combines with the one beneath it and the result is essentially a single paint-layer. The gloss builds with each new layer, too. There will likely be no need to varnish this work when I'm done. I should mention that if any section of this painting does, in fact, become solid or cured, overpainting upon that 'dry' paintt with a solvent wash will likely cause sinking as well as fissuring in the new layer. The way to safely accomplish any such addition would be to apply a thin but pure coating of ORIGIN to that cured area first; then painting-over that treatment stops any tendency to fissure. This is the only instance where the adjunct of "oiling-out" would be needed.

Below: I sat down at the easel with plenty of morning light coming through my north-light window. What a difference to the camera images: The painting is absolutely glowing with innner-illumination. I left and came back to the work numerous times, simply refining the overall work which was quickly but broadly-established yesterday. Refining means applying detail/accents onto the 'set' but still 'wet' undercolorings. If I wait too long and the paint physically solidifies ("dries"), then I invite a loss of the inner glow.

Below: Detail of water showing rigger-applied solvent-thinned washes of light-blue and yellow-green to indicate waves. [Note: A "rigger" is an olden term for a long and thin sable or squirrel-tail "line", or "liner" brush.]

Application of some thicker opaque (YO+IR+Z) highlight to the cliff rocks.

Next image: Finally, two days after I thought this thing was done, I refined the sky by placing shadows and highlights upon the clouds.

Anyway, it's fini. I'll just call it "Mid-Day". Overall, the tempera technique is rather quick in execution. I spent little actual painting time --maybe 2-1/2 hours total --on this small scene, leaving it then returning whenever to put a few more strokes/details in. The final work has a pleasing gloss and an overall brightness that rather astounds the eye. Warning: as per Hunt's advice, placing another wash-layer over the now-dried painting will obscure the light ascending upwards from beneath the primarily washed-on coloring. If you wish to 'paint-in', apply a layer of white first; allow that to set, then glaze atop that, mingling the glaze into the white just a titch-- something it will do pretty much by itself. As for adding shadows, just go ahead and wash-over that coloring to the work where shade is desired. This act will effectively obstruct the inner light. There is a final warning. Paint which has not fully cured, though appearing dry or tacky to the touch, will suck the binder from your over-paint, causing a fissuring situation where applied washes shrink and pull-apart, especially if the superimposed paint is thicker as opposed to thinner. To help allay or remedy this effect, apply a layer of pure ORIGIN to the un-cured paint first; or add extra ORIGIN to your paint when you make it up; or paint very thinly, instead.

PS: concerning the above image, taken outdoors and showing a warmer hue: I've left plenty of kilobytes and weakened the compression in this last image, and so if you do a 'right click' on your mouse and select "view image" then a likely larger-than-life-size view should open.

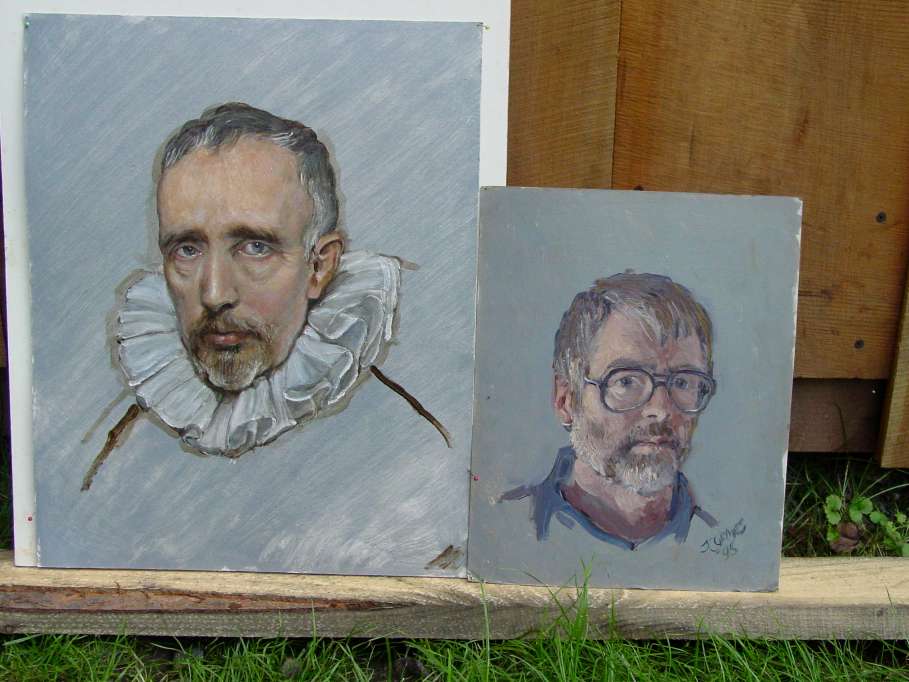

Above: A comparison showing two paintings, side-by-side, both created with ORIGIN; however the duller work on the right was painted-over again in order to improve detail; and this was performed well-after the initial painting had dried. What had originally been a glowing scene became just commonplace -- a lovely view but ....dim. Look at the two paintings carefully. The difference between these two works is striking as regards their intrinsic illuminative power. Even when you ignore the bright blue VS grey skies, the brightness of the left painting done in washed-on layers applied successively while set but still 'wet' proves Holman Hunt's cautionary advice concerning any repainting after the work has dried. Detail may improve but that 'inner light' is lost. There is a way to accomplish the feat, but that involves the use of an intermediate "heightening" with white. Performed one-section-at-a-time, detail and illumination can be had in this manner.

Blending, Modeling ...Melding.

Is this little painting too roughly performed for your taste and sensibilities? Are those boulders in the foreground built with forceful and bold strokes too .... callous? Is smooth definition and refined modeling your cup 'o tea? Then know this: At any time during the painting process-- and up to about a month afterwards -- extreme smoothness in modeling of form, light and shade and color can be increased by the simple act of "blending". Well, a much better word for this action would be "melding", but that requires some explanation. I'll now share something rather novel with you ...

"Blending" is an act so common to 'oil painting technique' that it would seem to be unimportant to even mention herein. In fact, blending can be performed in several ways. Examples: The painter can blend colors on the palette before applying them. A painter can also blend color on/ within the painting, as long as the paint remains "wet" or mobile. Blending can also happen when layers mix "optically', meaning you see the combination of tints by the visual mixing thereof; though this feat is not an actual mechanical mixing of the colors, at all.

As regards egg tempera painting, "blending" can mean something rather different. The primary modus operandi of the egg tempera craft is the ability to apply innumerable thin layers of paint -- layers that quickly build and refine objects towards a level of realism Cennini considered far better than that obtained via wall or oil painting. "If you would paint the Madonna, you must use secco", Cennini wrote. Why? Oil painting was cumbersome and slow to dry. But with egg tempera, the thinly-applied layers set quickly, allowing further layers to be added.

Here's the downside: Blending tints is easy with oil; but blending is neigh impossible with egg tempera.

It is not that the tempera painter cannot mix colors before laying them on; and, of course, blending can also occur optically -- which is another hallmark of the craft. But that third process of blendng whilst the applied layers are wet, well, that becomes a problem. The paint layers dry too quickly to allow much of that mechanic, excepting within the first layer. Applying then blending subsequent layers is tricky and fraught with danger. Thus, a most desirable trait to secco would be a way or manner of combining the numerous thin paint-layers --layers that have 'set-up' but are as yet not physically dry. It can't be done, really -- and this is why Vasari mentioned the fault in his story of Jan van Eyck and Antonello da Messina. Water may be the universal solvent but in this situation its solving action upon set-up egg-bound paint is only partial. The water does not truly solve the under and over-layers so as to easily combine or "meld" the layers together. Instead, the layers may very likely swell, tear and crumble; and what a mess to fix. Thus, this particular form of 'blending' has always been a hazardous act with egg tempera. Again, as mentioned above,Vasari wrote that many painters had tried in vain to find a way to blend ("meld") applied layers by somehow combining wall painting (pure basic oil painting) with tempera painting (this combo is termed "tempera grassa"); and, until the van Eyckian discovery of a "wonder varnish that dried in the shade", these experiments towards improved blending ...failed. To this day, tempera painters have instead continued to meld paint-layers by the cumbersome act of 'hatching' colors with the brush, which is a rather petty gimmick for optical-blending.

Melding" layers of paint is an invaluable aspect of blending that has been truly lost to painting history and especially oil painting-technique. Nobody does it anymore, really. Melding of paint-layers would be a great thing if it were allowed within the tempera technique. As for the oil technique, within that realm the notion is quite unheard of.

But my point in covering all this is that this act of 'melding applied and set layers' is easily performed when using ORIGIN and a preferred solvent. I performed this simple, desirable, amenable and corrective artistic procedure numerous times in that more-carefully rendered 24x30-inch landscape painting at the top of this web-page. As was done with the above demo, objects were painted quickly and brusquely; then melding was performed, and with clever results towards realsim. The actual mechanic is simple, for you see, the solvent I used nicely solves pre-set ORIGIN-bound paint-layers, allowing an actual and deft melding thereof. Regular oil painters schooled in today's common techniques will not appreciate this re-solving of the paint. No, they are used to blending while all is 'wet'. Your average oil painter of today might even view this solving of the applied paint as a troublesome happening. For the basic oil enthusiaste, blending occurs upon the palette and also within the fresh paint layer; that's it. By contrast, using ORIGIN with a tempera-like method of oil painting, blending can occure in all manners; and the cleverest painter will use the melding of applied layers as his/her ultimate weapon towards realism. And what a tool that is! As long as the solvent is still able to soften the paint, melding can occur and recur at whim. Rubens also mentioned this very action when he told Mayerne, "In order to make your colors spread easily, and consequently unite well ... dip your brush lightly in clear essential oil of Venetian turpentine*...." [* A solvent comparable to gum spirits of turpentine which Rubens said was extracted through boiling of the Larch balsam with water and distilling the vapor.]